West Ashley neighborhood is one of the state’s oldest African-American communities

The community of Maryville, also known as Maryville/Ashleyville, is a place with a history that goes back to when the boat landed from England in 1670. The specific history about the development of the village, later the Town of Maryville and currently the community of Maryville/Ashleyville is an ever-evolving work in progress.

The community of Maryville, also known as Maryville/Ashleyville, is a place with a history that goes back to when the boat landed from England in 1670. The specific history about the development of the village, later the Town of Maryville and currently the community of Maryville/Ashleyville is an ever-evolving work in progress.

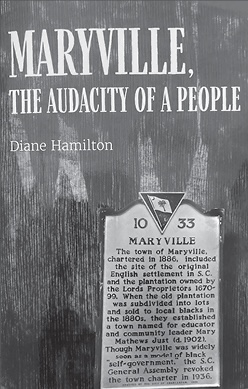

The rich picture of this historic African American narrative begins to come into focus from researching the historical newspapers; reading Kenneth R. Manning’s book Black Apollo of Science: The Life of Ernest Everett Just; digging into the archived documents at the Avery Research Center for African-American History & Culture and discovering Maryville, South Carolina: An All-Black Town and it’s White Neighbors a thesis presented at Harvard College in November of 1995 by Allen Carrington Hutcheson as one of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors; or purchasing and reading Diane Hamilton’s recent book entitled Maryville: The Audacity of A People.

In addition, there are three other opportunities to explore the narrative: 1) a video display with the same name, “Maryville: The Audacity of A People”, at the IAAM which is based on Hamilton’s book; 2) the “Maryville and Frederick Deming Jr. Industrial School” section on the Preservation Society “Charleston Justice Journey” website; and 3) soon to be installed historic markers at the new Carr-Richardson park located on the Ashley River in Maryville.

The town of Maryville was laid out on land along the Ashley River that was originally the “experimental plantation” for the colony. Governor Joseph West’s palisaded home stood near the intersection of Fifth Avenue and Main Street in the 1670s. Fifth Avenue followed the original road to the palisade; therefore, qualifying it as one of the oldest roads in South Carolina.

In the late 1880s the land was divided and sold to African-Americans who were earning money in the phosphate mines or as day laborers on farms. One of the original land owners was a woman named Mary Just. In Hutcheson’s thesis he speaks of the difficulty in determining the details of the original foundation and development of the town due to the lack of records and thus the inability to corroborate personal recollections. He even addresses the two historical contradictory versions of the town’s name: “one white and one black.”

Hutcheson states: “One is the work of a white genealogical historian, Henry A.M. Smith, who in one sentence gives the widow of C.C. Bowen the credit, or rather blame, for having the land divided up and sold out to negroes. The other published account is in the biography of Ernest Everett Just, a distinguished black biologist of the 1920s who was raised in Maryville.” Ernest’s mother was Mary Matthews Just. She worked in the phosphate mines and “negotiated a solid investment in one of the sought-after plots in the village in 1888.”

In Kenneth R. Manning’s biography of Ernest Just, Black Apollo of Science: The Life of Ernest Everett Just, Manning uses Just’s letters as supporting evidence that the town was named for Ernest’s mother, Mary – “she became a strong community leader, canvassing the inhabitants, mostly men, and persuading them to transform the settlement into a town.

They called the town, Maryville, after its prime mover.” One fact that has come to recent light, Mary Just didn’t live in the community at the time of its naming. In her book, Hamilton adds additional perspective to the role the two Marys played in the history of Maryville, it is a complex subject. At this writing, there is no absolute proof for any version of why or how the village/town/community came to be known as Maryville.

Mary Just had a passion for education and felt that the town of Maryville needed a school. She sold property to found the Frederick Deming Jr. Industrial School, the first industrial school for African-Americans in South Carolina. She also instilled this passion in her children.

Mary’s son, Ernest, took the spark she instilled in him and excelled in the academic field, graduating magna cum laude from Dartmouth College with a zoology degree, special honors in botany and history and honors in sociology. In 1916 Ernest Just received his doctorate in experimental embryology from the University of Chicago. Dr. Just achieved international acclaim and his research in the field of embryology is considered fundamental. He did this despite the racism and prejudice that was the norm for his day.

Today Just’s accomplishments are recognized and celebrated each February when the Medical University of South Carolina hosts “The Ernest Everett Just Symposium”, a fitting tribute to a native son.

In the late 1920s, the landscape of St. Andrew’s Parish began to change from rural to an area attractive for suburban development and the town of Maryville acutely felt this pressure. In a legal battle, where few documents remain, the town’s charter was revoked by the South Carolina state legislature.

By 1936 the town of Maryville was officially declared nonexistent and the area now came under the jurisdiction of the magistrate and police of St. Andrew’s Parish. Annexation into the City of Charleston followed late in the twentieth century continuing a trend in the Parish that had begun in the early 1960s.

Stories about Maryville? Contact Donna Jacobs at westashleybook@gmail.com.