Violent crimes in West Ashley saw a sharp uptick in 2021

by Bill Davis | News Editor

Twenty twenty-one has been a dubious year for violent crime in West Ashley. Phone trees light up whenever shots are heard in a neighborhood. Social media posts explode after every rat-a-tat-tat.

The hue and cry over recent gunfire and crime in West Ashley has gotten so intense that Charleston Police Department Lt. Heath King, who is the commander of the police Team IV which patrols this part of town, released a public comment.

He didn’t mince words.

“There has been an obvious uptick in violent crime recently,” he intoned before stating that the department has dedicated investigators to disrupt “the networks” creating the problems.

He lamented that many of the violent offenders have been arrested “over and over again … but continue to get released.” King pointed to a single day, Nov. 2, as an example of how busy his team can get with 327 “calls for service” that day alone in West Ashley.

It should be noted that a call for service can be as dangerous as a bank robbery, and as milquetoast as a treed cat.

It should be noted that a call for service can be as dangerous as a bank robbery, and as milquetoast as a treed cat.

Pressed for comment afterward on what he meant by “networks,” King was equally blunt, saying they were criminal “gangs.” He would not comment on the names, location, or other identifying information of the gangs as investigations are ongoing.

Chief of Police Luther Reynolds is working with legislators and courts to have repeat offenders stay in jail longer so the city can “get some clean time,” according to King.

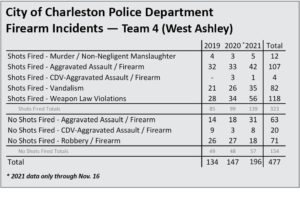

The department recently tracked eight categories of violent crime over the last three years, and in some areas the uptick is obvious, while at least one has slowed.

Take for instance the increase of weapon law violations incidents that involved shots fired. In 2019, there were 28; in 2020, there were 34, an almost 25-percent increase in a year.

But in 2021, the number jumped to 56, exactly doubling the incidents in two years. And consider that those numbers were culled on Nov. 16, and there was still a month and a half to go, and that number could further climb.

Incidents of aggravated assault involving a firearm where no shots were fired climbed from 14 in 2019 to 31 so far this year. But incidents of robberies involving a firearm with no shots fired dropped from 26 in 2019 to 18 so far this year.

Chief of the S.C. State Law Enforcement Division Mark Keel recently echoed King’s call for sentencing reform, saying it “often only serve(s) to incentivize criminal conduct.” He further said his state agency needs “legislative support and community involvement to improve public safety and keep our streets safe.”

King says Charleston is far from the only city to see increases in violent crime, as the rest of the country continues to deal with ripples of the Covid outbreaks – high unemployment, damaged economies, more people home for upward of a year, and the availability of guns.

Keel’s SLED reported this summer that South Carolina had notched its highest murders total in a year up to that point.

The Pew Research Center, quoting federal Centers for Disease and Prevention statistics, said murders rose “dramatically” nationally in 2020, but for unclear issues. Pew also saw aggravated assault rise close to 12 percent between 2019 and 2020, and that violent crime rose nearly 5 percent over that same 12 months.

Perhaps luckily, South Carolina was in the bottom-third of murder rate increases nationally.

State Sen. Gerald Malloy (D-Hartsville) isn’t so sure that the “one size fits all” solution of lengthening prison stays for violent crime is the panacea that King and Keel present. Malloy is the past president of the state’s trial lawyer association, as well as the leader of the state’s last sentencing reform bill.

Malloy defends the sentencing reform effort he led that lightened sentences in some categories and gave judges more discretion, saying it was based on “best practices, research, and statistics.”

“There has been a long debate whether or not to ‘lock’em up’ or have a rehabilitative system in a state that believes in redemption,” says Malloy. “If you have a ‘lock’em up and throw away the key’ model – one, you have to pay for it, and two, you have to be consistent if it happens to your son or someone you’re close to. There can be no ‘Uh oh, he’s a nice boy.’”

Malloy says that if the problem is parochial and truly isolated to gang activity, there are anti-gang laws in the hands of the state Attorney General, and perhaps the Charleston Police Department should coordinate with state agencies, like Keel’s SLED for answers.

Malloy says that if local officials want to support a “knee-jerk” solution like lengthening jail stays “without an evidence-based approach … it’s probably not going to work going forward.”