A deeper dive into World War II prison camp helps separate fact from folklore

The Prisoner of War Camp stories have provided many years of intrigue and urban legends for St Andrew’s Parish. Divining out the truth has taken persistence. Between “old school” face-to-face conversations and “new school” googling for digital archives the story about the prisoner of war camps in St Andrew’s Parish is becoming more complete.

The Prisoner of War Camp stories have provided many years of intrigue and urban legends for St Andrew’s Parish. Divining out the truth has taken persistence. Between “old school” face-to-face conversations and “new school” googling for digital archives the story about the prisoner of war camps in St Andrew’s Parish is becoming more complete.

Now for P.O.W. camp Version 2.0.

The stories of watching prisoners march from the train back to the camp; seeing the double-wired fence and the lights of the camp from bedroom windows; prisoners contracted out to pick vegetables on local farms; prisoners staying in the community after the war and marrying local girls; and after the war locals gathered in what was the dining hall to form a local Supper Club all feed the imagination of St. Andrew’s Parish.

The one tidbit of urban legend that has never surfaced to reality is that there were Japanese prisoners housed in the camps in St. Andrew’s Parish.

Now that the chimney, which was part of the guards club house, succumbed to the wrecking ball there is little that remains along Colony Drive to remind the community of not only the horrors of the war but the day to day impact of the prisoners on life in St. Andrew’s Parish.

But the prisoners were not always housed on Colony Drive as it turns out. The story from a resident of Windermere about “watching prisoners march from the train back to the camp, seeing the double wired fence and the lights of the camp from bedroom windows” was intriguing. Colony Drive seemed a little far away for that visual.

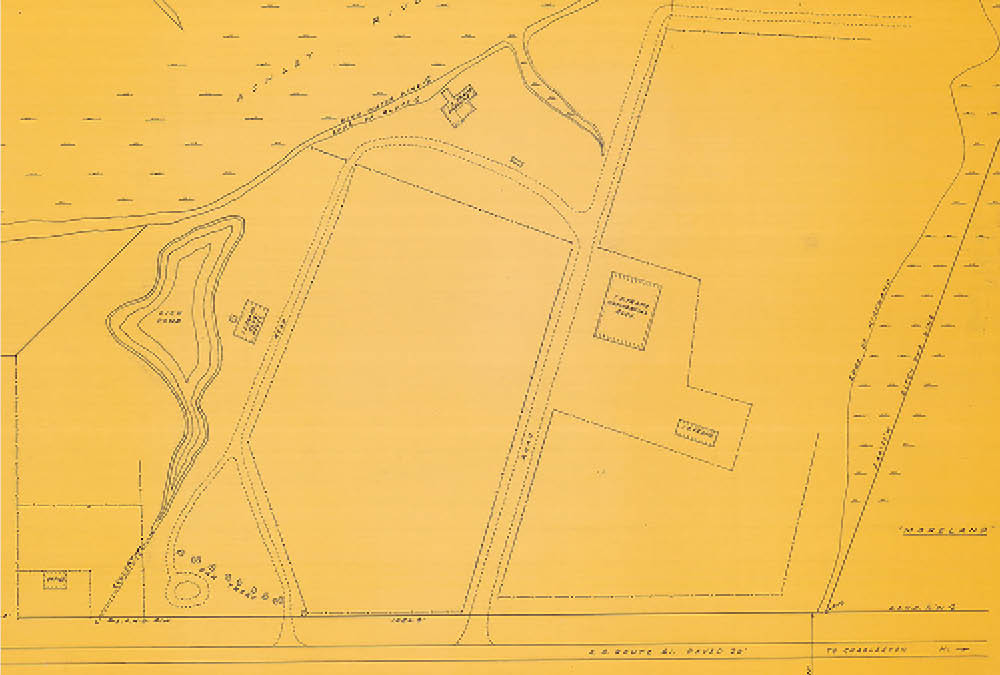

One story was told that the camp was once on the land that would become Westwood in 1950. The confirmation of this location came in the discovery of a newspaper article that ran in The Charleston Evening Post on Dec. 27, 1943. The headline read: “More Italian War Prisoners Coming Here”.

In the article it was stated: “The camp will be moved from its present site on U.S. Highway 17 to a location on the Ashley River.” A subsequent article appearing in January 1944 placed the location “near Windermere”.

In addition, the article fleshed out more details that help unwind the urban legends: 1) about 500 men were housed in the camp; 2) “The men were brought here in October to help met the acute labor shortage.”; 3) originally the prisoners were expected to be of German descent, but all have been Italian; 4) the prisoners were mainly contracted to work on farms to gather crops, in the fertilizer mills, or at the paper mills; 5) Contractors were assessed 10 cents per prisoner as laborers to pay for the utilities at the camp.

In the January 1944 article, we learn that the land for the new camp is on the river, surrounded by trees, higher elevation and leased to the army rent-free by the West Charleston Corporation.

Plans for the dedication of the camp with a program of entertainment that included a softball game in the afternoon followed by a program of music in the evening were detailed in a June 1944 article.

By July of 1944 the articles that ran in both The Charleston Evening Post and The News & Courier detailed conditions in the camp — there are recreational opportunities described; the treatment of the prisoners — they were paid in coupons that can be exchanged at the canteen; and the problems with sabotaging vegetables — Germans cut swastika symbols into the tomatoes they were hired to harvest. The subsequent investigation discovered only one tomato was marred and yet this urban legend found its way to a recent recounting. And yes, now the camp houses Germans. The majority of whom were in Rommel’s Afrika corps.

Although the Germans signed the peace accords in May of 1945, prisoner of war labor continued through March of 1946 according to a Jan. 9, 1946 article in The News & Courier. Arthur W. Bailey, Charleston County labor assistant under the emergency farm labor program described the rigid regulations that governed the use of this labor force. Prior to the end of the war, prisoner labor accounted for 15,000 days over 20 farms.

Now only 50 prisoners were working on five farms. P.O.W.s would only be allowed to harvest crops planted in 1945. Further evidence of the use of prisoners as farm laborers resides in the papers of Charles Ravenel, housed in the archives of the SC Historical Society.

There are contracts for P.O.W. laborers hired for use on his truck farm and Arthur W. Bailey signed many of these contracts. (This former farm will soon be the location for the new Old Towne Creek County Park.)

After the war ended, a provocative headline ran in the Aug. 22, 1948 edition of The News & Courier: “Secrets of the PW Camp Here Told.”

Some of the “secrets” told were: 1) West Charleston Corporation headed by I.D. Peek and Cotesworth P. Means leased the camp to the army in 1943 and Major Vincent returned the land in 1946; 2) a “full-fledged romance” blossomed between some American girls and the prisoners; 3) Captain Vincent was the camp commander and lived in Byrnes Downs; 4) once three prisoners escaped and made it to the army air base at Ten Mile where they stole a jeep, “set out at a furious clip for Savannah” but were caught in Beaufort; 5) the prisoners dug a hole under the recreation building and were making a tunnel to the Ashley River; 6) an Italian prisoner secretly married an American girl and though sent back to Italy, he ultimately returned to live in Charleston with his wife.

As time passes, the legends, tales and secrets have borne out real stories.

Do you have St. Andrew’s Parish P.O.W. camp stories? Contact local historian

and author Donna Jacobs at westashleybook@gmail.com.